Hey guys,

I'm still ploughing away at Fightland. Back from holiday and got a chance to write a big traditional martial arts piece on the factors which affect the development of martial arts disciplines. These are always fun for me to do, and I should have a part 2 coming soon.

Hope you don't mind clicking the link, and as always all feedback is welcomed!

Cheers,

Jack

The number of traditional martial arts techniques which have been written off as ineffectual, but which are now reappearing in mixed martial arts bouts, is growing by the day.

Just last week we saw Jon Jones demonstrate a traditional ju-jitsu shoulder lock from within the clinch. The overhook americana or ude garami was always a cool technique in self defence demonstrations, but it was never thought that someone would pull it off so effectively on a resisting, world class mixed martial artist.

http://i.minus.com/ibjY8t7unwLoEg.gif

It was a technique developed with one purpose, self defence, but Jones applied it in a competitive, sporting environment.

http://s2.glbimg.com/VS3QQkaFp5Z21QG9ozAYP6XeY0g=/top/s.glbimg.com/es/ge/f/original/2014/05/03/untitled-126.jpg

Similarly, a few years back, Shinya Aoki applied a classical winding armlock or waki gatame with great affect.

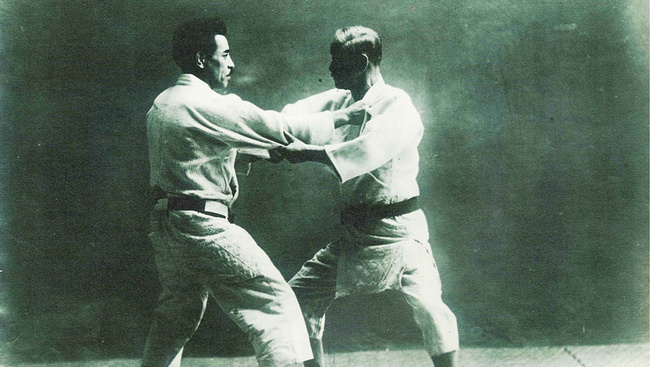

Here's Jigoro Kano, a jujitsu expert and the father of judo, demonstrating the same technique.

And here is Kyuzo Mifune demonstrating it in his master work The Canon of Judo.

How Techniques are Developed

There are two main variables which affect the applicability and development of techniques. The first is how they are practised. Training without a resisting opponent and against unrealistic, lazy attacks like the stepping punch of karate or zombie-like lunge that is common in aikido is just training the mechanics of a technique, without being able to actually manufacture or recognize the opportunity. The more you work with an opponent who will counter and deny your techniques, the further down the path you can go and develop further techniques and strategies.

The second variable is the intention of the technique. Certain techniques are much more suited to certain situations than others. While you have heard a thousand times "real kung fu / karate / aikido / capoeira / river dance is too dangerous for MMA". A lot of the time it is just complaining and excuse making, but there is truth in some cases.

A finger lock or eye gouge could save your life, but both are banned in MMA because they are disproportionately effective and rapidly damage athletes. And I'm not saying they shouldn't be banned--I don't want fighters to have two or three fights before their hands and eyes are so busted up that they have to retire.

While some traditional martial arts techniques are illegal in MMA, plenty are not and just haven't been utilized yet. Hell, there's plenty of techniques prevalent even in amateur wrestling which haven't found their way to mainstream MMA yet. But when you have a world class mixed martial artist, training with other world class fighters every day, and creating opportunities to apply these techniques, pleasant surprises come fast.

Today (and in the follow up part of this series) I want to talk less about mixed martial arts applications, and more about the catalysts which spur martial arts to develop in specific directions. The impetuses for the development of new techniques. In the traditional martial arts world there have been methods for use on the battlefield, for arresting rowdy drunkards, for protecting oneself from banditry, for protecting others and even for situations as specific as fighting on uneven ground or at night.

Every culture has it's own fighting traditions, but their intention determines which techniques are prevalent within these systems.

Life and Death in Jujitsu

The first catalyst for development is perhaps the greatest spur to creativity: fear of death.

In a street fight or a scuffle outside the bar someone could die, but it's rarely the objective of any party involved. You don't square up and swing punches if you genuinely want to kill someone. No, we're talking about martial arts in the context of warfare. As the Cold War demonstrated--nothing forces advancements in science as fast as war.

Let us not forget that martial arts are traditionally arts for war. Miyamoto Musashi, the great Japanese swordsman, lists use of the musket and horsemanship as martial arts. It could be said that any method taught to soldiers is a martial method.

One of the most important arts to our modern day MMA was jujutsu ("the soft art"), a traditional Japanese fighting method. Before evolving into judo and Brazilian jiu jitsu, jujitsu was considered a battlefield martial art and it was the property of the samurai, the warrior class of feudal Japan.

Brilliant action scenes in movies have us convinced that battles involving swords and armour are about running from opponent to opponent, slashing them, and moving on as they fall. Of course, a katana can take your arm or head off, but then what would be the point of wearing all that restrictive armour if you were just going to get sliced in half by the first blow regardless?

No, battles between armoured infantry were ugly events anywhere in the world. Swinging a sword at someone in plate armour causes the sword to act more as a slightly pointed bat. While Japanese armour was lighter than full plate armour, it was still an extra 50-60lbs slowing the movement of whoever was wearing it, and combined with the wearer's own sword, it provided good protection.